At the conclusion of the portfolio reviews, each reviewer is asked to note three outstanding projects. Their selections are then tallied to determine that year’s PhotoNOLA Review Prize Winners. Rich Frishman was awarded the 2018 PhotoNOLA Review Prize, which includes a solo exhibition at the New Orleans Photo Alliance Gallery during the fourteenth annual PhotoNOLA Festival, a cash award of $1000, one year of complimentary mentoring and strategic marketing consultations with Mary Virginia Swanson, and a $2000 credit with Edition One Books to create his own publication.

2nd Place winner, Meg Griffiths received a Santa Fe Photographic Workshops gift certificate, and 3rd Place winner Colleen Fitzgerald, along with the others, will be recognized with a feature on Lenscratch.

“Rich Frishman uses his camera as a tool of preservation by photographing the physical remnants of institutional racism. “Ghost of Segregation” is a poetic illumination on America’s complicated racial history.” – Richard McCabe, Ogden Museum of Southern Art

“Working with conceptual still lifes, where light and ephemera shimmer into new incarnations, she reveals that there is a beauty in the transitory nature of life, in those liminal spaces between the spectrum of emotions and events that come with being human.” – Aline Smithson, LENSCRATCH

“I was reminded of the memory of film and the allure of the latent image. Her landscapes, no longer traditional despite their nostalgic (for me) New England scenes, bent and folded and then scanned and printed into wondrous shapes on the paper. Transformed is what they were. They seemed to be weightless one moment, and so incredibly solid the next. The desire to hold the original object is compelling, but then so too is the desire to look at the series of images printed in succession and to move with them along the wall as they shift and flutter and float. Mesmerizing.” – Ann Jastrab, Center for Photographic Art

PORTFOLIOS

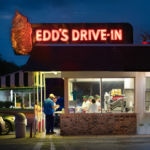

Rich Frishman

GHOSTS OF SEGREGATION

Our built environment is society’s autobiography writ large. Because we rarely consider our constructions as evidence of our priorities, beliefs and desires, the testimony our landscape tells is perhaps more honest than anything we might intentionally present. All human landscape has cultural meaning.

We often take our daily environments for granted, but within even the most mundane edifice may lurk an important bit of history. That stairway apparently to nowhere once went somewhere. The curious palimpsest of bricks covers something. What purpose did they serve?

My photography project, “Ghosts of Segregation,” explores the vestiges of America’s racism evident in the built environment, yet hidden in plain sight: Schools for “colored” children, theatre entrances and restrooms for “colored people,” lynching sites, juke joints, jails, hotels and bus stations. While much of the images are from the Deep South, prejudice has no geographic boundaries, nor is it limited to blacks and whites. Fear and tribalism has led to the stereotyping and dehumanization of many: Hispanics, Asians, LGBTQ, anyone who is perceived as “the other.”

Past is prologue. Segregation is as much current events as it is history. These ghosts haunt us because they are very much alive today.

BIO

Born and raised in Chicago, Rich Frishman studied with artists Reed Estabrook, Robbert Flick and Art Sinsabaugh at the University of Illinois, where he received a BA in Communications. He is a natural storyteller with roots in photojournalism, and those ethics still inform his work.

Rich Frishman’s photography is held in private and institutional collections, including the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, the New Orleans Museum of Art, and the Amon Carter Museum. His work has garnered awards, including two Sony World Photography Awards (2018), the 2019 Curator’s Choice Award from Review Santa Fe, Communication Arts Photography Award (2018), Photo District News Photo Annual (2018), Michael H. Kellicutt Award, International Photo Annual Award, and Critical Mass finalist twice. Houston’s Biennal FotoFest will feature Ghosts of Segregation in their 2020 keynote exhibition at Spring Street Studio, Ten by Ten (formerly Discoveries of the Meeting Place.) He was nominated for a Pulitzer Prize in 1983.

Frishman lectures around the US, including the New Orleans Museum of Art and Sony Square in New York, about the intersection of the designed environment, history and social issues.

***

Meg Griffiths

SOMEWHERE WITHIN AND WITHOUT

Somewhere within and without attempts to subtly shift and deconstruct the ways in which we engage with space, time and perception in the aftermath of trauma, such as the birth of a child, a separation, or the death of a loved one. Using everyday household objects as a point of grounding in and departure from the familiar, these scenes mark the strangeness that is experienced in the wake of particular loss— whether that loss be one of the self or others. There is an oddness in this liminal space, waking each morning to come into the reality that you are not the same person you were now that someone has gone or someone has arrived. The spatial and temporal dimensions of existence are forever changed. Drawing upon personal historical experience, these image serve as a metaphoric distillation of love, loss and connection, a finite offering to contemplate these discordant and poignant transitions.

BIO

Meg Griffiths is a Texas based artist and educator. Her photographic research currently deals with the domestic relationships and personal historical identity. Her work has been shown internationally, including: PhotoZurich, Barcelona Biennial for Fine Art and Documentary Photography, Pingyao International Festival of Photography, Chaing Mai Photo Festival, Columbia Museum of Art, Museum of Living Artists in San Diego, and Griffin Museum in Boston.

She was recently published on the cover of Oxford American and Focal Plane Journal. Her first monograph, Casa de fruta y pan was published in 2015, and Zatara Press published a collaboration book entitled Nothing that Falls Away in 2018. Collections include MOMA, Museum of Fine Art, Houston, Duke Archive of Documentary Art, and the Virginia Museum of Fine Art.

Her honors include the Julia Margaret Cameron Award for Best Fine Art Series in 2017, and being named one of PDN 30’s: New and Emerging Photographers in 2012.

Meg is currently the Assistant Professor and Area Head of Photography at Texas Woman’s University in Denton, Texas.

***

Colleen Fitgerald

STAMINA

Stamina provides new approaches to conventional subjects by utilizing the materials and tools of photography in non-traditional ways. A unique physical process combines aspects of sculpture and photography, subverting the idealized two-dimensional photograph and providing a new entry point to the enduring photographic subjects of natural landscapes and seascapes.

To create the images, unexposed large sheets of positive film are cut and formed into three-dimensional shapes before being exposed inside a camera outfitted with a custom film holder that accepts the film as a three-dimensional object instead of as a standard, flat sheet. The results on the shaped film can appear stretched and distorted. In other instances, sheets of film are bent into shapes after exposure. Once the film is developed, it is re-photographed on a lightbox and printed. The final product of the land and seascapes pictured in these ways contain physical gestures and seem as unusual as they are familiar.

The folded, curved, cut, and overlapping sheets of film create an immediate awareness of the materiality of the photograph and remind the viewer they are not looking at the landscape itself, but a deliberate construction of it arranged by Fitzgerald. The process reconstructs both reality and the very material that records reality. In doing so, the final product of the photographic work is not a direct representation of the world, but a negotiation of vision.

BIO

Colleen Fitzgerald is a New England based visual artist. Her work creates new approaches to conventional subjects in art by utilizing the materials and tools of photography in non-traditional ways. ArtsWorcester of Massachusetts selected her as the recipient of the 2018 Present Tense Prize for artistic innovation, risk-taking, new practices, and excellence in execution in art. She was chosen as the 2016/17 Artist in Residence at the Noble and Greenough School and a visual arts resident at the Vermont Studio Center and Virginia Center for Creative Arts.

Colleen earned a Master of Fine Arts from Parsons School of Design and a Bachelor of Arts from Boston College. She has also studied at La Scuola Lorenzo de’ Medici in Italy and Massachusetts College of Art and Design. She delivers talks at institutions across the country and exhibits work internationally. The Society for Photographic Education, Filter Photo Festival, Pingyao Photography Festival, and more have featured her work. She also enjoys curating exhibitions to champion the work of fellow artists.

Colleen has served as a faculty member at Endicott College, Eastern Connecticut State University, the University of New Hampshire, the University of Maryland – Global Campus, Memphis College of Art, and Parsons School of Design Teaching Assistantship.

***